Looking back on his long and illustrious career in the field of participatory budgeting, Alan Budge speaks to us about how he got into PB, his highlights and advice for making participatory processes sustainable. After more than 25 years promoting PB, there is a lot to say. Alex King, Shared Future’s communications lead, asked the questions.

How did you get into PB?

“I remember Hilary Wainwright, the editor of Red Pepper, gave a lecture in the Bradford Resource Centre, where I was working at the time in a sort of community development capacity. She had just been to Porto Alegre where PB started and had just written a book, Reclaim The State: Experiments in Popular Democracy, which had a chapter on PB in Porto Alegre.

“Hilary was talking about it, and for me it was a lightbulb moment. I was like, ‘this is amazing, why isn’t everybody doing this?’ Since then I’ve just followed the work.

About that time I was seconded to Bradford Vision while I was working at the Resource Centre, a local strategic partnership who had funding to support development across organisations within Bradford – they were actually experimenting with it themselves independently of me. There’s a film, Clean, Green and Safe the Participatory Way, which is a record of that very first event where they had up to £600,000 to distribute to clean green environmental initiatives across the city in two tranches: £300,000 in spring 2004 and £300,000 in the autumn of that year.

“It was peer to peer grant-making, with community organisations voted on each other’s projects. So it wasn’t pure PB; it wasn’t an open audience. But it still had this wonderful sense of the community being actively involved in making financial decisions, you know?

“Following on from that I went to Paris. Elaine Applebee, who was the chief executive of Bradford Vision at the time, had been invited to a PB symposium in a place called Bobigny, this disadvantaged area of Paris. This was November 2004. She asked me if I wanted to go and I said yes.

“It was the afternoon session of this symposium — you know the graveyard slot after lunch when everyone’s losing the will to live? My mind was just wandering and I wrote down the question to Elaine on a napkin, should we film the next event which was on the second tranche of £300,000? Because the first one would be fantastic and otherwise nobody knew about it because there would be no record of it.

“Elaine said yes, so we got this film-maker and I worked with him to sort of storyboard it and put it together. He did all the technical stuff, you know, and that was our first go at making a PB film. It was really good fun putting that together and I’ve worked on a few sorts of promotional films since and I love that aspect of it.”

There’s been lots PB happening around the world. How much of it have you seen in the UK in your time, besides Bradford?

“New Labour, between 2006 and 2010, put a lot of resources into developing participatory budgeting initiatives through the PB Unit. It became part of their program of government under Hazel Blears MP’s time at Communities and Housing secretary.

“The unit, run by Church Action on Poverty, was funded by the Department for Communities and Local Government, and there were some pretty high up officials in there who supported us. We used to have regular staff meetings at the office of the deputy prime minister down in Victoria. It was very much a part of the government’s policy.”

“At that point, we could go out and offer our services free at the point of delivery to whichever local authority was interested; I worked with Mansfield, there was work in Luton, some work in Redcar.

“And it was cross-sector. Like a lovely project at Redcar Housing Association up on the Northeast coast which I supported. It happened because we could offer our services free of charge because the government was sponsoring us to roll the program out.

“All that stopped in 2010. The PB unit dissolved after David Cameron’s administration came in. I left Bradford Vision, went freelance and we started up PB Partners, as part of Shared Future, to keep PB going.

Which sector do you think has the most potential when it comes to PB?

“PB has always been opportunistic and I mean that in the best sense of the word. If there’s an opportunity, you can do PB. If there’s some money available to put into a budget, if you’ve got political permission in the organisation to do it and if you’ve got the infrastructure to deliver it you’re in business.

“Town and parish councils are a really interesting example. We’ve just finished a project in Winsford. We did a bigger project with several town councils in north Yorkshire ten or 12 years ago.

“What’s interesting about parish councils is that they have something known as a precept which is a local tax they raise to deliver local community services. The parish council precept in Winsford and in north Yorkshire ten or 12 years ago was set aside for PB. They had, maybe, £250,000 a year. It’s a virtuous circle; people pay in, then they decide how it gets spent.

“It’s sustainable too. The problem with PB, and the reason it’s often run into the ground after two or three years, is that the money runs out, the funding stream dries up, and people can’t find funds to keep it going. With parish councils, however, the money’s always there. There was a nice guide written on parish council PB I’d recommend people read.

“But the main piece of work I was doing around that time, and where I think there’s big potential, was with the police. I worked with Greater Manchester Police in 2014 which was struggling with organised crime and they wanted to do something about that. The go-to person in those communities is often the criminal, you know.

“So the police put the funding in, saying to the communities, ‘look, we’re here to support you. We’re literally putting our money where our mouth is.’

“At the voting events, the chief inspectors of each of the divisions hadn’t had anything to do with any of this. They were very hands off because it was far below their pay grade. It was the sergeants and the foot soldiers who had made it happen.

“But the senior leaders all came to the event and they couldn’t believe it. They were confronted with a sea of happy, enthusiastic looking people. Their jaws dropped. They’d never seen anything like that before. GMP even had to employ another officer afterwards, because the intelligence that was coming in on the back of it was just so much greater.

Are there any other sectors where PB works well?

I also think the health sector has enormous potential. And we’ve done work with statutory and voluntary sector providers around health initiatives over the years. For example, we did a project in Scotland in 2016 to provide respite support to full-time amateur non-professional carers for people with disabilities. So they became the voting audience. These carers turned up at this event and voted on what sort of initiatives would help them, whether it’s people coming in to support them, whether it was trips out, more food.

“And it was incredible. These were very busy people with massive demands on their time. But they all turned up. They all voted. They all took part in it because it meant something to them. And the fact they could actually come together, literally in the room, talk to each other about their experiences and their war stories and all the rest of it was a really powerful event. It’s one of the most moving ones I’ve been to. The potential is always there sometimes, in the little nooks and crannies you wouldn’t necessarily expect to find it.

Like climate change? Is a climate themed PB possible?

“Another more recent highlight over the last couple of years was these four workshops around the country, Bristol, Manchester, Brighton, and Edinburgh, looking at PB and climate change which Jez Hall and I ran. We wrote a report called ‘Our Money Our Planet’. One of the things that came out of that for me very clearly was that all these local authorities were declaring climate emergencies. But what were they actually doing about it?

“My view around all this was that if we were to go to councils, and we did have some exploratory conversations, and suggested they run workshops like the clean green safe stuff in Bradford, small scale environmental improvement initiatives at a community level that could be voted on.

“If you set up programs of that nature in your local areas, we said, it would take a very small amount of money to get it off the ground but you would have an audience that will be coming to it. They’ll be interested in taking some action on climate and on the environmental challenges. You would also have a forum where they could start to talk to each other and become more aware of some of the more strategic aspects of what might need to happen next.

One really exciting idea is the potential of PB funded from power grid generators or community energy. Do you have any thoughts on that?

“As I say, PB’s opportunistic, if the will’s there and the finances to make something happen. If there’s a willingness to explore a new area, then absolutely. I think it’s surprising where some of these initiatives have come from.

“One of the nicest projects I worked on was that at Lichfield diocese. A guy there just thought, this is great, let’s do it. And he pulled it all together. They had received church funds for community wellbeing so decided to spend it on PB. They got in touch with us and asked if we could come and help them. It was just fabulous. You never know where the next one’s going to come from.

“For me, pushing something like climate themed PB would give it a really strong hook for people to link to and connect with. It can seem a bit nebulous otherwise.”

Funds from power grid generators themselves, or wind farms and hydro schemes, would be guaranteed money year after year?

“Definitely. And I think that’s interesting as well. What people worry about with PB is that you’re sort of salami slicing your existing shrinking budgets. And they think that we can’t do PB anymore because budgets have shrunk. But actually a percentage of 1% of a hundred million is still 1% of, you know, 50 million. It’s still 1%, you know?

“I think it’s actually a lot easier if you’re coming in with a new sort of initiative to build PB into it from the ground floor, rather than trying to sort of tap into an existing set of funding requirements, you know, so psychologically I think that’s much more helpful. So the energy thing is a good opportunity.”

“PB is a great recruiting tool. Over the years, PB events have shown time and time and time again that brand new people, who have never been involved in anything before in their lives, will come along. They come because the money’s on the table. It’s not everyone’s cup of tea to sit down and look at documents but there’s a few people who will do it.”

How do you see PB sitting alongside citizens’ juries?

“I think there is a direct link between PB, and citizens’ juries and assemblies. But it’s a moot point as to which comes first.

“Let’s look at it is this way. You ask people for their ideas at a sort or public assembly. Ideas can come from suggestions made around broad themes of individual projects. Then you deliberate and improve them, and they can then go out to a PB vote. This is what I call an egg timer model, or figure of eight model. The starting point is a broad consultation with the community about the sorts of things they would like to see delivered under themed headings: what we’d like for housing, or health or community safety. Just generate lots and lots of ideas.

“Citizens’ assembly, citizens’ jury and PB – you can see it sitting sequentially in any order, depending on where your entry point is. They’re profoundly linked.”

“The middle of the figure of eight is where the most popular ideas are worked up for feasibility and checked for accountability, legality, budget, all that sort of stuff. That would be more of the sort of citizens’ jury; a smaller group of residents involved in unpacking the detail. So if you ended up with 50 great ideas to start with, they would look at them and maybe whittle them down to 20 ideas. Then you put those stress-tested proposals back out to the wider community with a final vote. Citizens’ assembly, citizens’ jury and PB – you can see it sitting sequentially in any order, depending on where your entry point is. They’re profoundly linked.

“However, my passion is for PB because it makes a massive difference when people are trusted to spend some money themselves. And the danger with citizens’ assemblies is that the findings are kicked into the long grass and forgotten about. If the money is spent, then it’s spent and you can’t argue with that. But I do think they have an absolutely key role to play in terms of informing national and local government policy, and also creating citizen involvement to produce financial outcomes.

“Obviously, in terms of mainstream participatory budgeting, we’re not talking about a community group building a motorway or new hospital, but they will commission services from the mainstream providers and the service provider will then deliver the work. Citizens will have a choice over which of these projects are approved and that’s the classic model from Porto Alegre – citizens commissioning services from the mainstream providers – rather than smaller DIY community initiatives. So, if you can attach that deliberative aspect to PB, you could link it to a significant financial outcome quite easily. It’s been done many, many times.

What is your main critique of the way PB is done in the UK?

“One of my mantras is that the process is owned by the participants. Dundee’s participatory budgeting programmme, where they spent £1.2 million of mainstream funding, will look very different from Newcastle’s participatory budgeting program where they spent half a million quid or whatever, because circumstances on the ground are different. It’s ideally up to local citizens which mechanism they want, which order they want to design it in, how much involvement they want of different tools at different stages. Our job is very much facilitating that shared sense of shared enterprise.

“I think the main problem has been a lack of sustainability, of repeating PB, and there are two reasons for that. One is, as I said above, budgets change and disappear. But the bigger problem in practice is that it’s a very intense piece of work. I’ve been at the sharp end of delivering a PB program myself and I had to take a month off after! It’s hard work.

“Very often PB has been delivered and it has been fantastic. But then the enthusiasm isn’t there to build it back into next year’s work plan because of the amount of effort involved. People often say their day job has suffered, that kind of thing. That is where leadership matters.

“We did a debrief with Greater Manchester Police after a project there wrapped up and somebody asked a very simple question: was it worth it? One of the police officers involved in delivering it said that from the community’s point of view it was absolutely worth it. 100%. They loved it. They want more of this. But from the police’s point of view, there were serious questions they had to answer about whether this was the best use of their time.

“We did a debrief with Greater Manchester Police after a project there wrapped up and somebody asked a very simple question: was it worth it?”

“My response has always been well, actually, whether it’s the police, housing, healthcare, or a local authority, you have outcomes baked into your job description where it says you need better community engagement, better community relations. So you should see PB as part of your day job, not something extra. That’s the way to make it sustainable. PB’s never really established itself and that’s the main reason. I think people have just thought, ‘we’ve done that now, let’s just move on, and forget about it for the time being’.

“The thing about Scotland was the government pushed it and they said, you know what, here’s all this money. And our infrastructure support and the commitment to spend 1% of local authorities budgets by 2022 and all this kind of stuff. There are even local authorities in Scotland that employ PB officers. Porto Alegre has 16 districts and each one had its own PB officer. They put the resource into making it work. That’s what’s always been missing. That’s how it becomes sustainable – resourcing and support.

“There’s been a number of people over the years who have opposed PB tooth and claw.”

“I think when there’s been an isolated case where community organisations have taken on the PB delivery themselves, that’s been great. There’s been officers in Scotland that have carried it on year on year because they think it’s really important. Line managers have supported them in that work. It’s not a requirement, so it’s very much down to the goodwill and the enthusiasm of the people on the ground to keep making it happen.

“There’s been a number of people over the years who have opposed PB tooth and claw. They’ve hated everything about it. In my experience, that’s mainly because they’ve had a very nice little community set up themselves where they were the gatekeepers. They knew everything. They’re the ones that had all the funding streams.

Are there any other PB highlights you’d like to share with us?

“The Scotland PB work was extraordinary, a real privilege. The Scottish Government had decided that PB would be a great way to maintain levels of democratic engagement on the back of the Independence referendum, and would eventually commit to at least 1% of all council budgets to be spent through PB by 2022. PB Partners were commissioned to provide training and technical support to PB initiatives across the country.

“Jez and I had to cover the whole of Scotland. I got Orkney, the Hebrides and the Shetland Islands as part of my beat. And it was just fantastic! It was great personally to be able to get to know the country. With the Zoom culture we have now, you know, I don’t think that would happen in the same way. I wouldn’t be travelling to the Hebrides to do a two hour meeting any more, it would be on Zoom.

“Another highlight was the work we did on Dundee Decides, where they spent £1.2 million of the mainstream council budget. Now the entire budget of Dundee Council is £300 million. So they’d already got one third of the way to the 1% requirement just by doing that. So it shows how you can do it relatively painlessly. It can happen. So that was good in and of itself.

“The programme was rolled out into each of the city’s eight wards and the council’s in-house engineering department generated a selection of projects based on an initial consultation that had taken place before we got involved. This boiled down to a list of eight projects per ward with enough money to actually pay for four projects per ward. When I saw that list, I thought we’ve cracked it. Because this in a way was work that the council may well have delivered in any case. It was on their sort of long list, as it were.

“But it was fantastic to actually do the work, to turn these ideas into deliverable, costed projects, and to say to each of the ward areas, ‘you’ve got 150,000 pounds in your ward to spend. Which one do you want?’ And then for the community development team to take out their iPads into the community, into the schools, into the community centres and into the libraries — you can do it online as well, but there was an outreach aspect to it too — they had drop-ins. I went to one morning coffee event, where they just piggybacked on the back of that and asked people there which one they wanted.

“There were some staggering statistics. Like 70% of people had never been involved in community development stuff before. Things like that were coming out. 96% of them thought it was a great idea. These were really powerful endorsements of what had happened.

“But the minute that list of projects appeared for people to vote on and for the council to deliver on their behalf, I felt we’d cracked it. This is how you can do mainstream participatory budgeting.”

What do you think you learnt most from working in Dundee?

“The one thing that people picked up on afterwards was they wanted to provide more input at the design stage of the project. So when the projects were actually coming on to the chief engineer’s desk, they felt at that point, they’d have liked some conversations with the departments about how the projects would sit, what they were going to do, all that sorts of stuff, which is great because that’s what we want. It’s that figure of eight model which I was talking about. They wanted input at that point as well, as well as the top of the bottom.

“70% of people had never been involved in community development stuff before. 96% of them thought it was a great idea.”

“Dundee then said it would have a fallow year and regroup because it was a big piece of work. I don’t know whether they’ve done it again. And that’s what I’m talking about. That organisational inertia can creep in. But it was just such a powerful example of how PB can practically be scaled up which I was very happy about.

“We had a members’ briefing with elected members, to get the idea across to them. And a lot of people in the room were saying, ‘well, we should have some control over this.’ We’d then have to say to them, as subtly as possible, ‘with respect, you control the other £299 million. The £1 million is for the community to decide. Is that okay?’ And they went, ‘yeah, okay, we can do that.’”

You mentioned working in the Scottish Islands. What was that like?

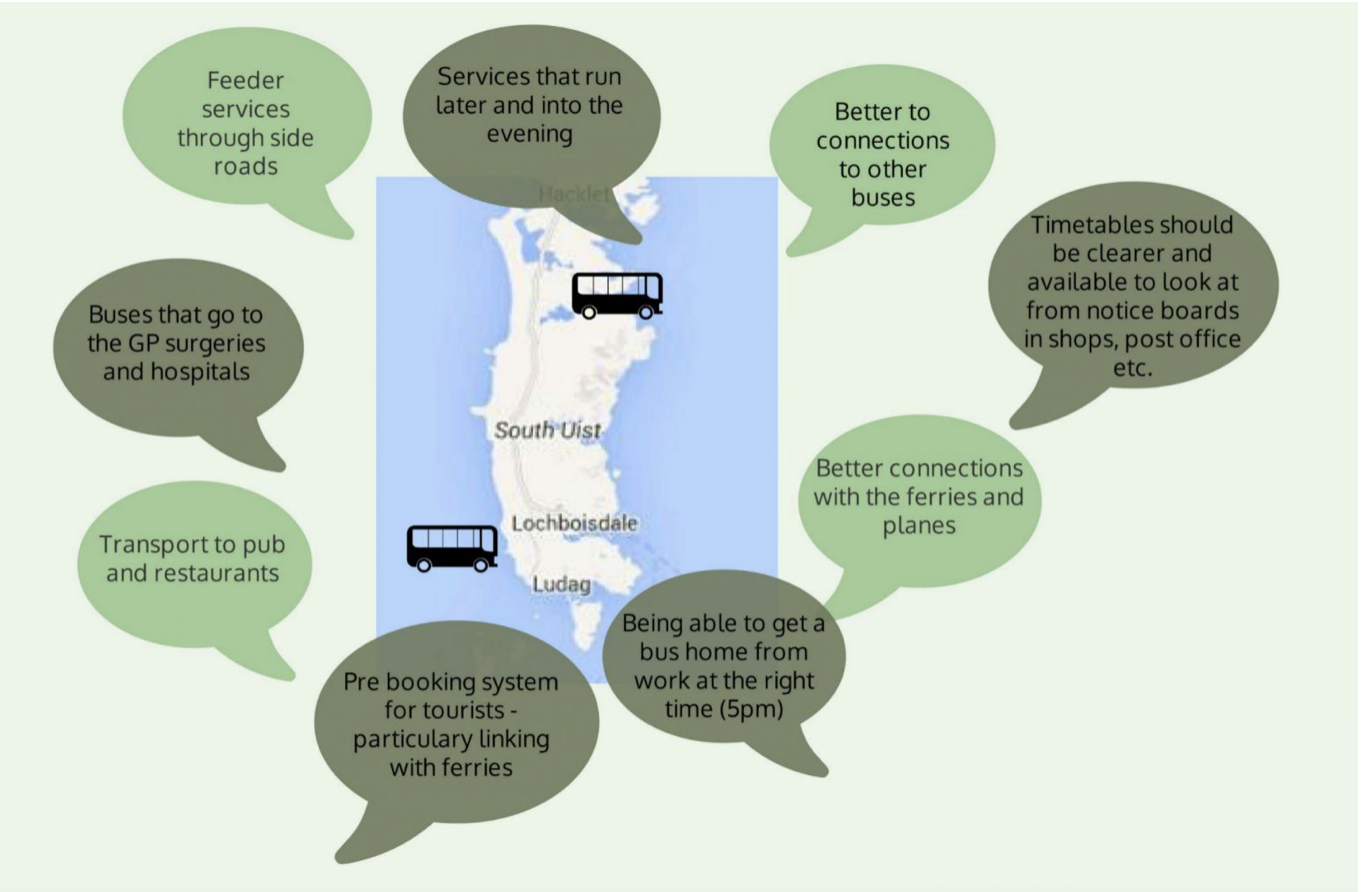

“Yes, my other highlight was in the Outer Hebrides where bus services tenders were up for renewal. We put the tenders out to the community to work on and vote on rather than the in-house transport department, deciding who was going to be awarded the tenders.

“It was being driven by the procurement department and the woman responsible for procurement was brilliant. You could just tell she got it and she really ran with it. And the community development sector as well. They worked in partnership to make it happen.

“The transport department thought we’d gone mad. They literally thought it was ridiculous. You can’t possibly even think about doing this. It’s going to end up in complete chaos. So that was a hurdle that had to be overcome.”

“In the two southern islands, Barra and Uist, the tenders come around every three or four years. They’re renewed and usually given to a different company. So those tenders are up for renewal and I think four or six companies put in bids and there were two tenders. So there was a genuine choice to be made. There was a community survey done beforehand, so the tenders were filled on the back of some community information that the company has been given.

“All of a sudden these tender documents appeared in my inbox. I opened them and had a panic attack. They looked so complex. It wasn’t just fares and timetables; it was environmental impact, community impact, fleet size, fleet description, questions around whether we could use taxi services, whether we’d attach bicycle ramps on the back of the buses. There’s a lot of technical information.

“So we took this out into the community. They weren’t that well attended. There were like half a dozen, six or eight people at each one. The transport manager sat in as well. Now that was a weakness. It was the winter, it was the first time we’d done it and I think people possibly felt exposed too because they were being asked to make complicated decisions.

“Anyway, we met with them and they went through each of these tender documents with a fine tooth comb. They asked intelligent questions. The transport manager was there as a sounding board and to answer technical questions, and I was asked to facilitate the dialogue.

“They came up with two of the four or six proposals. And at the end the transport manager said, ‘well, I’ve got no problem with any of these decisions, they’re robust’.”

“He might have decided two different ones, but the ones that were decided were perfectly fit for purpose. And it was okay.

“At one point he said about one particular bid, you know, that the timetable looks perfectly good to me. And this kid – he was 16 – just came straight from school in his school uniform! He said, ‘well, this doesn’t work for me. I’m not happy with this, this timetable is no good for me, it needs to be changed’. He felt empowered to say that.

“And we’d set it up in that way so that nothing would pass this table without your approval. You know, you are in charge of them. They ran with it, you know, and it was really powerful. It showed me that normal, reasonably intelligent people can deal with things like this. They can get their heads around it. They can make it work. It wasn’t too difficult, and that’s the point because people in the high echelons will see that.

“It also changed the relationship between the bus companies, the drivers and the residents, because they knew that passengers had commissioned them. So they were much more open to dialogue. All that sort of stuff started to shift. The running joke at the time was that if somebody’s stuck waiting for a bus that doesn’t come for an hour and a half they’re not quite as pissed off as they would be otherwise because they asked for this.

“The people in the room, the half dozen people, became ambassadors for the decisions they’d made.”

“They knew why this bus company had been approved and what it was doing and what he was trying to achieve. So they became ambassadors for that decision, which is great.

“It was a real win-win all the way around. It went from a standing start and total scepticism, to delivering half a million pounds’ worth of services. It was a brilliant piece of work and I got to travel around the Hebrides, which was nice!”

“Whether it’s the police, housing, healthcare, or a local authority, you have outcomes baked into your job description where it says you need better community engagement, better community relations. So you should see PB as part of your day job, not something extra.”